It has been several years since I wrote about my parrots’ speech comprehension, and when I did so, I discussed only anecdotal evidence. I now realize that it might be useful to delve a bit more deeply into that topic, first discussing the formal studies we did with Alex, and then sharing another anecdote about Griffin and Athena.

It has been several years since I wrote about my parrots’ speech comprehension, and when I did so, I discussed only anecdotal evidence. I now realize that it might be useful to delve a bit more deeply into that topic, first discussing the formal studies we did with Alex, and then sharing another anecdote about Griffin and Athena.

When we started working with Alex, the first step in proving that we could demonstrate verbal two-way communication was to show that he could produce appropriate labels in appropriate contexts and transfer that production to various situations (e.g., to know that “paper” is the correct response to the small piece of index card that was the training sample, and then to understand that it is also—without training—the correct response to a large sheet of computer paper).

Demonstrating speech comprehension would not be enough; the reason was simple; many nonhumans comprehend some human speech—that is, it is clear to almost every dog owner that their dog understands certain words and commands, for example—“Sit,” “Stay,” “Walk.” Many dogs even understand a lot more (e.g., see Griebel & Oller, 2012). But such comprehension is usually just a simple association: the animal knows that they get a reward for doing a physical action in response to hearing a particular sound, but doesn’t understand that the sound can be used in indifferent contexts (e.g., when the owner talks about a walk taken while on vacation and the dog runs around and gets its leash, thinking that they will soon go outside).

Comprehension is necessary but not sufficient for full two-way communication. Too, all the chimpanzee studies at the time (e.g., Gardner & Gardner, 1969; Premack, 1971; Rumbaugh et al., 1973) emphasized production. However, as the research progressed, all of us in the field realized that production by itself also was not sufficient; for example, Savage-Rumbaugh (1986) showed that a subject that learned to produce a symbol in an appropriate context might not know what the symbol really meant and needed additional training to do so. For example, apes that could use a label to identify an object might not, when given only the label, find the specified object in a pile.

We believed that by using our modeling system that differed from the training given Savage-Rumbaugh’s apes, and which demonstrated both production and comprehension (as described in a previous blog), Alex had simultaneously learned both production and comprehension…but we had to prove it. Thus, we embarked on two studies that we hoped would allow Alex to demonstrate clear comprehension of his labels.

Alex Study #1

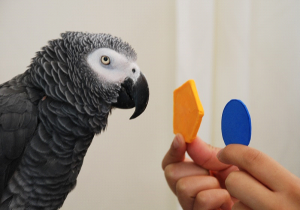

In the first study (Pepperberg, 1990), for each test trial Alex was shown a different collection (see Fig 1) of 7 physical exemplars (each collection chosen from among 100 objects of various combinations of shapes, colors, and materials) and—without any training—was asked 1 of 4 possible vocal questions, each of which requested a different type of information (e.g., “What color/shape is [designated object]?”, “What object is [designated color/shape]?”) about a single item in the collection; he was required to reply vocally to each question.

In the first study (Pepperberg, 1990), for each test trial Alex was shown a different collection (see Fig 1) of 7 physical exemplars (each collection chosen from among 100 objects of various combinations of shapes, colors, and materials) and—without any training—was asked 1 of 4 possible vocal questions, each of which requested a different type of information (e.g., “What color/shape is [designated object]?”, “What object is [designated color/shape]?”) about a single item in the collection; he was required to reply vocally to each question.

A correct response indicated that Alex understood all the elements of the question and could use these elements to guide the search for the single object in the collection that provided the requested information. He responded with an accuracy of 81.3%. Many of his errors were on labels that were somewhat difficult to distinguish vocally (rock/box—he produced “box” like “bock”) or to distinguish visually (red/purple) because of his UV vision, so the results, even though not at 100%, were compelling.

Alex Study #2

The second study (Pepperberg, 1992) was much more complicated: For each trial, Alex was shown different collections of seven items, each collection again chosen from among 100 items of various combinations of shapes, colors, and materials, and he was asked to provide (vocally) information about the specific instance of one category of an item that was uniquely defined by the conjunction of two other categories (e.g., “What color is the [object defined by shape and material]?”).

The second study (Pepperberg, 1992) was much more complicated: For each trial, Alex was shown different collections of seven items, each collection again chosen from among 100 items of various combinations of shapes, colors, and materials, and he was asked to provide (vocally) information about the specific instance of one category of an item that was uniquely defined by the conjunction of two other categories (e.g., “What color is the [object defined by shape and material]?”).

Other objects exemplified one, but not both, of these defining categories (see Fig 2). Alex responded with an accuracy of 76.5%. He made the same types of errors (confounding similar colors or labels) as in the earlier study. Notably, even though the questions were more difficult, the difference in his accuracy from the first study was not statistically significant. We also tested Alex on how well he comprehended his number labels (Pepperberg & Gordon, 2005) after he had demonstrated their productive use (i.e., labeled specific numerical sets exactly). I described all his number studies in an earlier series of blogs and won’t repeat that material, other than to say that his accuracy in comprehension was close to 90%.

Griffin & Athena Have Their Say

We have never formally tested Griffin or Athena on comprehension…remember that neither of them have the same extensive repertoire that Alex had. Instead, we’ve been doing more behavioral cognitive tests with them on topics like probability, liquid conservation, and inference by exclusion, comparing their accuracy to that of young children.

However, as I’ve mentioned previously, they both understand quite a bit of English speech and continue to surprise us with their abilities—even though what we can relate are only anecdotes. Such an example occurred last week. One of my research assistants (RAs) usually keeps the birds occupied in the mornings in the living room of the apartment where they live while another RA prepares part of their breakfasts (chopping fresh fruits and vegetables) in the kitchen, out of the parrots’ view.

On this particular day, the first RA unexpectedly had to do everything by herself, and the birds were quite upset at being alone; Griffin kept calling for her to “Come here” and Athena kept whistling and threatening to fly off her cage. Finally, the RA returned to the living room, asking them if they could see anyone else around, telling them that she was the only one there and that they had to calm down if they wanted their morning meal. They both looked at her, ruffled their feathers a few times, and started to preen. We really don’t know how much they understood, but they definitely changed their behavior