How do we know our threat reduction interventions are working and actually benefiting small cats and other wildlife? We could simply depend on nature. If threats are reduced, the cats can do the rest themselves. Nevertheless, monitoring is vital so that interventions and threat reduction actions can be evaluated and changed if necessary. If something is not working, we must know.

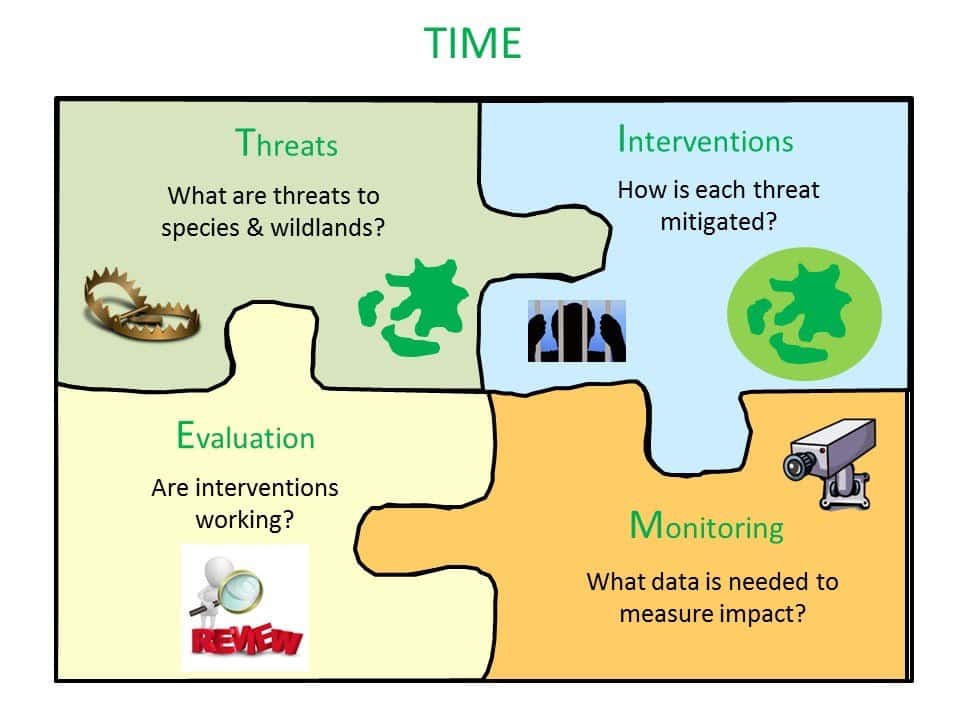

To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, numbers are necessary. We use a four-step feedback loop called TIME—What are the Threats? Apply Interventions to reduce these threats. Monitor the impact of interventions on the wild cats. Analyze the results of monitoring to Evaluate intervention effectiveness. Have threats, like viruses, morphed? If so, alter interventions if necessary and continue to monitor and evaluate. Constant vigilance is key.

Unfortunately, we cannot go back in time, but our method provides a positive feedback loop that continuously repeats. A simple example shows how TIME enables more effective conservation. I will use my own work with a cat called a guigna (gween-ya) in Chile as an example. Having established myself on Isla Grande de Chiloe off the coast of Chile, I interviewed residents and found that a small cat that they called “the little thief” was killing chickens. When the little thief killed chickens, more often than not, the little thief was eventually hit over the head with a broom handle and did not survive. You get the picture: easy prey, a dozen dead chickens, and one dead guigna.

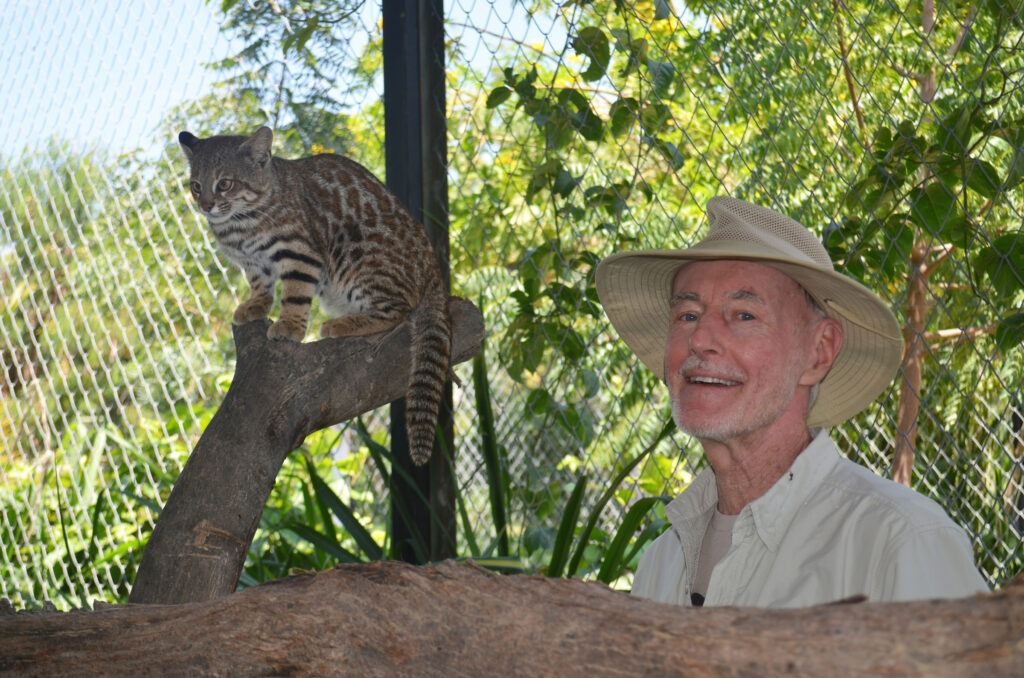

The Threat was a poorly constructed henhouse, or worse, none at all. To reduce the threat, my Intervention was to repair poorly built henhouses and, for free-ranging chickens, construct new henhouses. During my three-month career as a carpenter, I placed trail cameras in the local forests near residents’ farmhouses to Monitor the local guignas. Because I had never seen guignas alive, I could not help checking my cameras frequently. Sure enough, both male and female guignas were present. So began my first Evaluation. What was my very first discovery? Males, never females, were the chicken thieves!

Badru Mugerwa’s community-based conservation work on behalf of African golden cats in Uganda serves as another example. Badru knew that rural people depended on bushmeat for sustenance and income. The Threat to African golden cats and other wildlife was bushmeat poaching. Through community interviews and discussions, Badru was informed that residents knew how to raise and care for pigs. Piglets, it turned out, were simply too expensive to obtain.

With the help of the Small Wild Cat Conservation Foundation’s financial partners, Badru’s Intervention was to supply the local community with piglets. In return, the community agreed to reduce and eventually eliminate bushmeat poaching as the piglets aged and did what female pigs do best. Trail cameras were used to Monitor the local forest surrounding the village. Data collected from the cameras was used to Evaluate the effectiveness of the piglet program. The results were stunning. To reward good behavior and to spread the successful piglet program to more communities, Badru created a Mobile Dental Clinic to deliver dental services, something unavailable to rural villages, at no cost to residents. The Mobile Dental Clinic proved to be a powerful Intervention as well.

The above examples show that the proverbial carrot works far better than the infamous stick. Clearly, our interventions improved local lives. Improving the lives of community members instead of blaming, chastising, and making their lives even more difficult with anti-poaching patrols and arrests works best to achieve long-lasting conservation success. After all, anti-poaching patrols do not treat the root causes of poaching, which is a lack of food and money. In fact, patrols just make life even more difficult and thus promote resentment. Patrols are also not sustainable in the long-term since they must be paid for indefinitely.

We need only imagine if, for whatever reason, our local community leaders established roadblocks deliberately preventing you and me from driving to our local grocery store. With unrelenting resentment and a lot of effort and time, we would use every shortcut to walk to and from the grocery store. The roadblock would ultimately be deemed a failure. Instead, imagine our community leaders providing free transportation!

2 Comments